Displacement by Design

Portland is known for its parks, bridges, bicycle paths, microbreweries, and coffeehouses. Portland also harbors a complex and fraught history with racialized displacement. The Clackamas, Multnomah, and other tribes traditionally resided on the land, but the arrival of European settlers in the mid-19th century prompted mass displacement and sweeping away of the tribes.

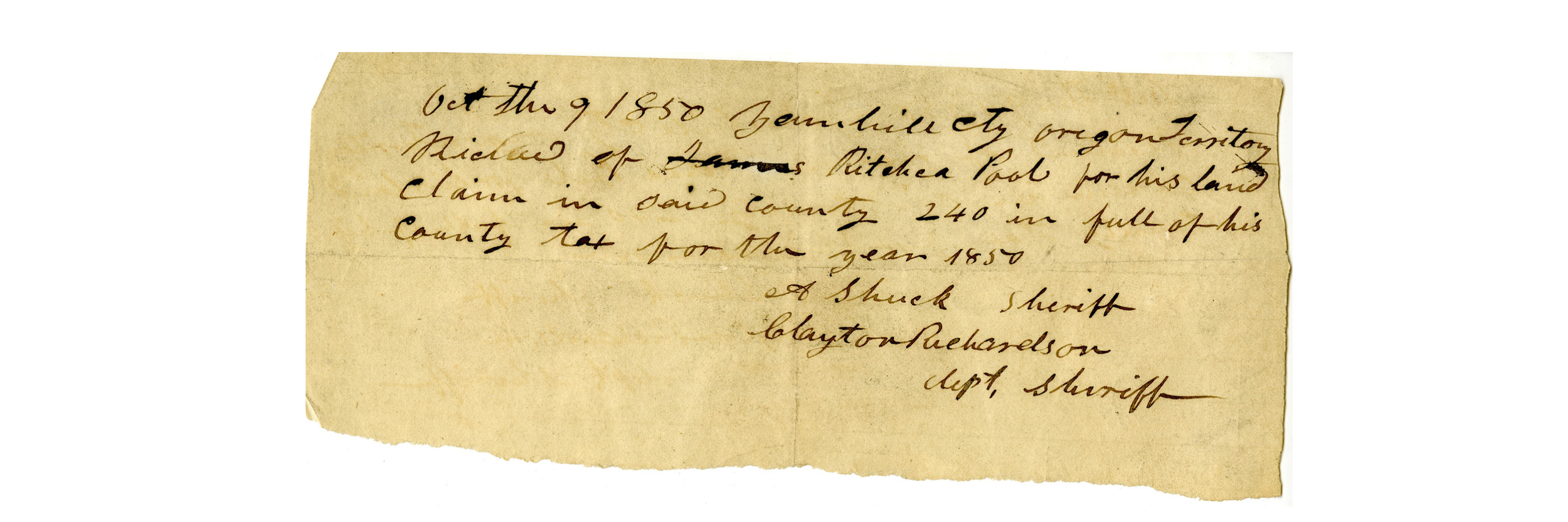

Through treaties and policies like the Donation Land Claim Act, Indigenous peoples were stripped of their lands, cultural practices, and livelihoods, leaving a lasting scar on the city's foundation. Members of various tribes were not considered U.S. citizens and could not own land under the law, even though Section 4 of the Donation Land Claim Act allowed “American half-breed Indians” of legal age who were citizens of the United States (or declared to be) to take Donation claims. Donation Land Claim Law also explicitly excluded Black and Hawaiian people, validating white settler claims in the Willamette Valley. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 severely restricted Chinese immigration, impacting Portland's burgeoning Chinatown. Add to this, discriminatory housing covenants and Japanese internment during World War II further marginalized Asian communities.

Tax receipt for a donation land claim, October 9, 1850

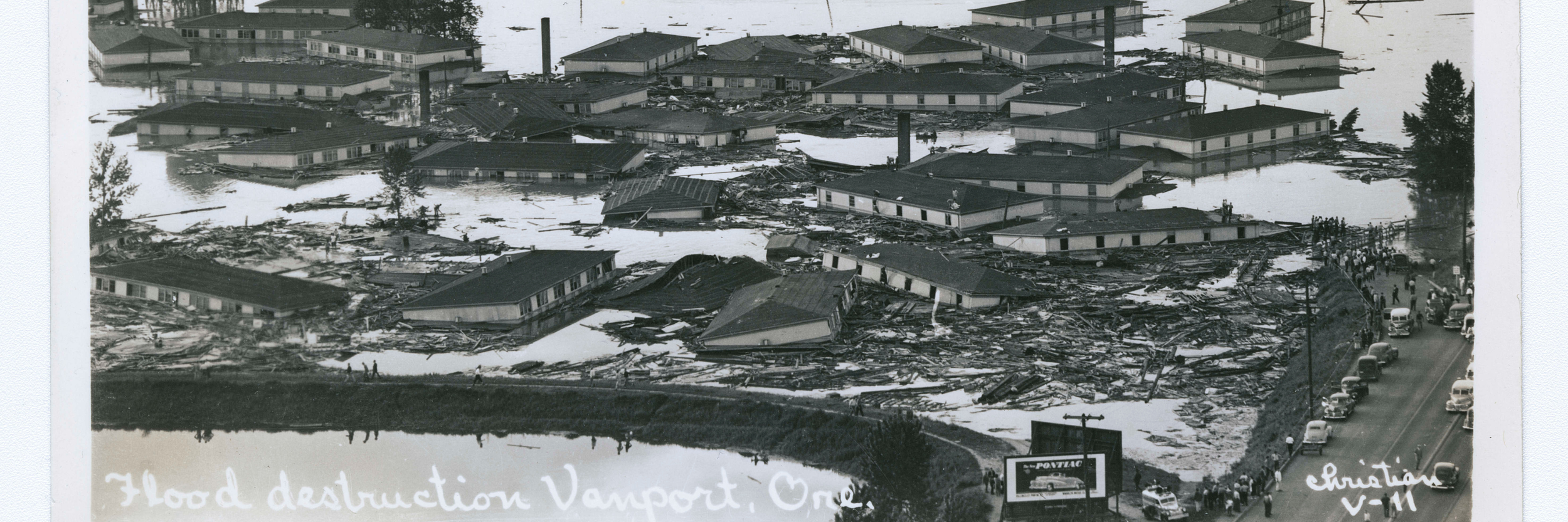

During the early 20th century, the government actively destroyed and neglected Black communities, like Vanport, furthering their struggle for secure housing. These communities, along with others, were subjected to redlining, a discriminatory practice where banks denied loans to residents in predominantly Black neighborhoods. Redlining hindered the ability to purchase homes and build generational wealth. Black people seeking to own homes also faced restrictive covenants placed in property deeds and titles. These restrictive covenants were supported by the government, landowners, real estate boards, realtors, banks and local neighborhood associations to enforce racial segregation of neighborhoods. Although they are no longer enforceable, many of these covenants can be found on deeds today.

Vanport, Oregon

Examples of racist covenants in Portland included:

“… No person of African, Asiatic, or Mongolian descent shall be allowed to purchase, own, or lease said premise …”

“… No Negroes, Chinese, Japanese, Orientals, or any person other than the Caucasian race shall rent, purchase, occupy or use and any building on any lot, except that this covenant shall not prevent occupancy by domestic servants of a different or nationality employed by the owner or tenant. …”

In the 1880s, Old Town Chinatown was a mix of sailors, longshoremen, and immigrant laborers. The first Chinatown was a few blocks away across Burnside Street on the Southwest blocks. The Chinese community left Second Avenue and resettled in the Northwest blocks because they were pushed out by the growing white population that discriminated heavily against Chinese society. As the city grew during the 20th century, immigrants found a haven in Old Town Chinatown.

The Depression and rising housing costs pushed many marginalized people to the edges into urban homelessness. The neighborhood became known as Skid Row for decades. Bud Clark, the 48th mayor of Portland, delivered meals to the men in the SROs and said the area was often a den of illegal activity.

By the 1980s, the city welcomed the construction of the Chinatown Gate, a gift from Portland's sister city, Kaohsiung, Taiwan. The gate became a visual marker and tourist attraction for the area. The inscription on the gate reads, “Four Seas, One Family” as a reflection of inclusivity.

However, Old Town Chinatown was declining and a new Chinatown, the Jade District, was growing. Some critics argued, at the time, that the gate was a symbol of gentrification and performative. Over the last 40 years, multiple attempts have been made to revitalize or gentrify the area.

Chinatown is undergoing another wave of gentrification. This time, we’re seeing an influx of proposals for sneaker factories and expensive restaurants. The gate is a reminder of the important contributions Chinese immigrants made to the city, but it is also a reminder of the challenges that the Chinese community, and other communities, continue to face as displacement continues.

Chinatown Gate

Understanding Portland's history of racism is crucial for acknowledging its impact on today. Even though the covenants and exclusion acts are no longer enforced or legal, displacement still exists due to a shortage of affordable housing, gentrification, and other economic factors like low wages, income stagnation, and inflation. Displacement often acts as a precursor to homelessness.

When individuals or families are forced out of their homes due to rising costs or gentrification, they often struggle to find affordable alternatives, potentially leading to homelessness. Policies aimed at addressing homelessness sometimes inadvertently exacerbate displacement. For instance, clearing encampments forces individuals to relocate to different areas, further disrupting their lives and straining community resources. Engaging with minoritized communities is essential to understanding the challenges and opportunities for creating effective solutions. At Sisters, we believe in community-based solutions.

In 2022, when I stepped in as the Acting Executive Director, Sisters was at a crossroads. We spoke with community leaders, friends, and internally to decide what to do. In the end, we chose to expand and acquired 331 NW Davis. However, not everyone in Old Town Chinatown welcomed the news. While some news outlets praised this new chapter in Sisters’ history, others criticized our move and even tried to thwart it. One business owner attempted to buy the building. Another business owner commented that we could have chosen another location in Slabtown.

What does this solve, other than making it someone else’s problem? We can either look at the sight of human suffering and say it’s bad for business, or we can acknowledge that our society’s inability to care for and meet the needs of everyone in our community is bad for business.

Portland has approximately 6,200 individuals experiencing homelessness on any single night. Addressing the root causes of displacement is crucial to developing long lasting solutions. This includes dismantling discriminatory housing practices, investing in affordable housing development, and addressing poverty.

Implementing long-term, holistic strategies that focus on prevention, intervention, and support services are crucial to creating a more equitable and just city for all. It’s going to take all of us, partnering in authentic relationships with one another to make this lasting change happen.

Love us. Hate us. We are here to stay.

Mural by p:ear at 331 NW Davis